We often say that nothing in art feels truly new anymore. Whatever appears on the front line seems to echo something already done, as if every attempt at novelty circles back to the past. This is not just cultural fatigue or a lack of imagination. It points to something deeper about how we see, how we remember, and how meaning itself is assembled in us. What follows is a reflection on why the new so often looks familiar — and why, within that very limit, a quieter and more interesting kind of new may still be waiting.

When we say that nothing in art feels truly new anymore, we are not really talking about a failure of imagination. We are touching something deeper about how human perception works.

Whatever we create and whatever we look at is seen through memory. The artist carries a lifetime of images, gestures, styles, and influences, even when trying to escape them. The viewer does the same. So when something appears, it is immediately measured against what is already known. It looks like something done before, because recognition itself depends on resemblance. Without reference, we would not even know what we are seeing.

In that sense, the “extraordinarily new” is almost impossible to recognise as such in the moment. Newness can only be perceived by being related to the old. The past is not just behind us; it is active in us, shaping how form, meaning, and novelty are assembled.

That is why the front line of art moves so slowly. Not because artists lack courage or ideas, but because culture, perception, and the nervous system itself evolve at a human pace. Styles change, materials change, concepts shift, yet everything still seems to echo what came before. The language of art, like any language, can stretch and bend, but it cannot be reinvented overnight without becoming unintelligible.

So, is there no way around this?

Structurally, no. As long as we see through memory, learn through pattern, and make meaning by comparison, anything new will appear as a variation within continuity.

But there is a subtle opening.

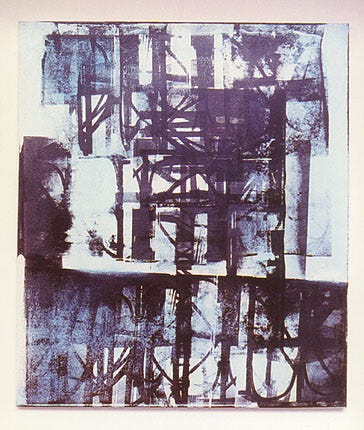

What can change is not so much the look of the work, but the source from which it arises. When art does not come from the urge to be new, or from recombining references, but from a different inner condition of seeing, then the work may still resemble what history already knows, and yet carry a different coherence. It may not announce itself as revolutionary. It may not look extraordinary. But it can feel strangely clear, quiet, or inevitable, as if the same reality is unfolding again, but through a slightly different alignment.

Here, the “same” does not repeat itself mechanically. It unfolds differently each time, because the human being through whom it passes is different. The new is no longer in the form alone, but in the way the form comes into being.

And perhaps this is a new kind of new we can celebrate.

Not the dramatic break from the past that declares itself as unprecedented, but the quiet discovery that even within the same patterns, the same echoes, the same lineage, something fresh can still appear — a subtle shift in coherence, a different gravity of presence. A reminder that novelty is not always about escaping what has been, but about allowing what has always been there to reveal itself again, just a little differently, now.

In that sense, the fact that art keeps looking like what came before is not a dead end. It may be the very place where this quieter, deeper kind of new is waiting to be seen.

Reference: