How a declassified U.S. Army study points to a deeper structure of perception

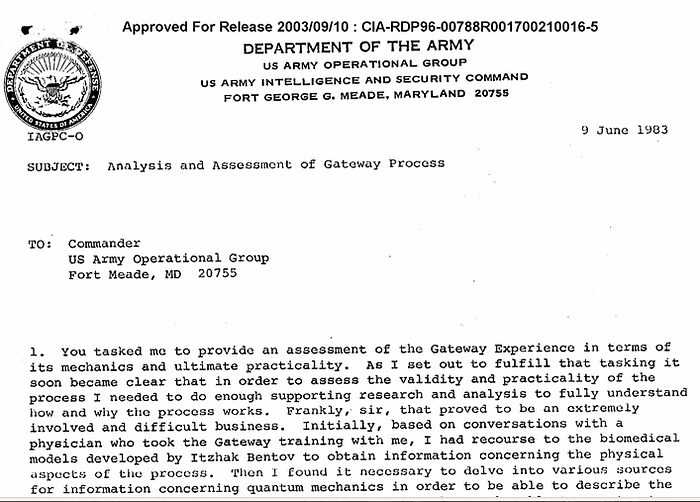

In 1983, an internal U.S. Army intelligence report set out to examine a strange claim: that human consciousness, when trained in a particular way, could step outside ordinary reality. The document, now declassified and known as Analysis and Assessment of the Gateway Process, did not begin as mysticism. It began as a military question. If reality is partly constructed by the mind, could altering the mind alter what reality feels like, and perhaps what it can access? Four decades later, that question reads less like science fiction and more like a quiet invitation to look closely at how experience itself is assembled in the brain–mind.

The Gateway report grew out of work at the Monroe Institute, where sound patterns were used to guide the brain into unusual states of coherence. The authors described the brain as a signal processor and consciousness as something that could shift perspective when the usual sensory and narrative structures were softened. In their language, reality was not taken as fixed. It was something the mind organised. When that organisation loosened, people reported timelessness, loss of body boundaries, vast inner space, and the feeling of stepping outside the world they knew.

The report went further. It tried to explain these experiences using the metaphors of its time, holograms, energy waves, resonance, and fields. It suggested that with training, awareness could detach from space and time altogether. Anyone, not just soldiers, might learn it. What mattered was not force or technology, but learning how to let the mind reorganise itself.

Read today, the document feels like a mixture of careful observation and speculative reach. The experiences were real enough. The physics used to explain them was more poetic than precise. Yet beneath the language, one simple insight keeps returning: what we call reality is not directly perceived. It is assembled.

This is where the Gateway process meets the brain–mind model.

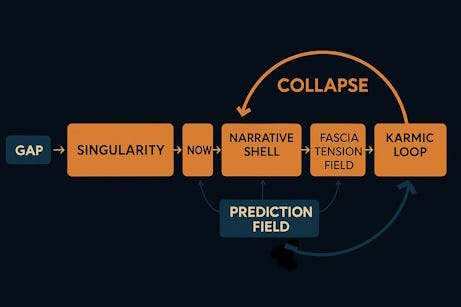

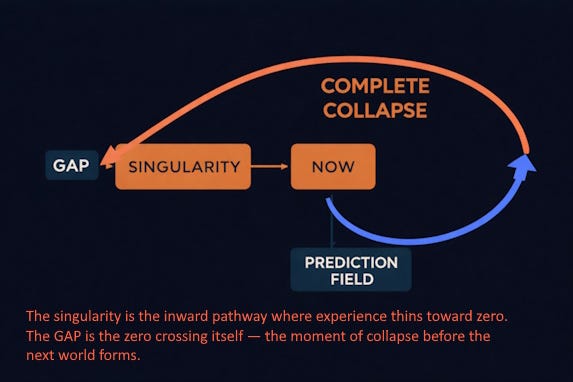

In the Brain-Mind Model framing, experience is built in cycles. Sensory data and bodily signals rise, narrative and self stabilise them, and then a collapse releases the structure before the next moment forms. This collapse is not an ending. It is a refinement, an exchange, where what is no longer relevant drops away and something new can enter. At the heart of this cycle is what you call the GAP.

The GAP is not a mystical void. It is a physiological–perceptual collapse window. A brief phase, on the order of a few hundred milliseconds, where the previous moment’s structure dissolves, and the next has not yet formed. Normally, this window is crossed so fast that it leaves no trace. The rebuild is immediate. The self feels continuous. There seems to be no rest at all.

But the Gateway report is, in effect, an exploration of what happens when that rebuild is slowed.

What they called dislocating from reality can be translated more simply as this: the narrative shell loosens, the sense of self thins, and awareness brushes the collapse window instead of rushing past it. From the inside, that feels like floating, expansion, timelessness, or being nowhere. From the brain–mind perspective, it is the system lingering near its own reset point.

This is why the sliding scale mind-spaces matter. Experience is not just on or off, narrative or gap. It moves along a continuum. At one end, the mind is dense with story, identity, memory, and expectation. As regulation improves and load reduces, the narrative softens. Thoughts slow. Boundaries become lighter. Time loses some of its grip. Closer still, interpretation thins and perception feels more open, less owned. Right near the threshold, the system keeps touching the GAP.

Here, the GAP becomes accessible as a mind space.

Not because the GAP itself is a place you enter, but because the brain–mind can hover so close to its own collapse window that each rebuild is minimal and each collapse is clean. Awareness keeps reforming near zero. From the inside, that feels like resting in open presence, a quiet field with no push to become someone in a world.

What is experienced in this near-gap mind space is not nothingness. It is an unstructured presence. Sensory gating opens wide, but labelling is quiet. There is seeing without a seer, hearing without a listener, being without a story. Because there is no narrative anchor, it is later remembered as emptiness or void. But in the moment itself, it is more like raw openness before you call it anything at all.

This explains the Gateway descriptions without needing to leave physiology. They were not finding a doorway out of spacetime. They were discovering what it feels like when the machinery that builds “me here in time looking at a world” goes quiet.

The report also emphasised training to remain there. In the brain-mind model language, that means learning to let the collapse complete while not forcing a heavy rebuild. Letting residue drop. Letting the next moment arise clean. Over time, the system learns that it does not have to rush back into identity. It can live nearer to its own baseline.

And this is where insight comes from, not as information arriving from elsewhere, but as re-patterning when the system returns. When you come back from near zero, the rebuild is different. Lighter. Less burdened. Old loops lose their grip. Something new can organise itself because the collapse was clean.

Seen this way, the Gateway report becomes less about extraordinary travel and more about ordinary structure seen clearly. It is an early, awkward attempt to name a simple truth: that the deepest frontier is not out there, but in the moment where perception releases itself before becoming a world again.

The brain–mind model keeps that frontier tangible. The GAP is a physiological–perceptual collapse window. The mind space near it is not mystical territory but the near-zero end of a living regulatory cycle. And what loosens there is not reality itself, but the story that usually convinces us that reality has always been solid, continuous, and owned.

In that loosening, something quiet becomes obvious. Experience can arise without a self. And when it does, the world, when it returns, is never quite the same.

This opening toward the GAP shows what becomes possible when the brain–mind learns to release its grip and rebuild lightly. But every opening has its edge. The same collapse that brings clarity can, if not met with a healthy return, loosen coherence itself. In the next piece, we will look at that boundary — at why staying too close to zero without a stable rebuild can become disorganising, and how regulation, not escape, is what allows this mind space to become a source of insight rather than instability.

Reference:

ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT OF GATEWAY PROCESS

What the Gateway researchers kept returning to, beneath their metaphors and speculative physics, was a remarkably consistent picture of direct perception. As people moved into deeper states, ordinary space and time no longer held their familiar shape. Time could feel slowed, stretched, or absent altogether. The body no longer felt like a fixed centre of experience, but more like a fading reference point within a much wider inner field. Experience was not anchored to “here” in the usual sense, but opened into something spacious and unlocated.

Along with this came a soft dissolution of self. Not an experience of nothingness, but of awareness without the usual scaffolding of identity. Participants did not report blankness. They described a centreless presence, where perception remained, but the feeling of being someone standing apart from it had thinned. In that state, experience felt less fragmented. The report speaks of coherence, of a sense that things fit together without effort, as if the mind were no longer breaking the moment into pieces to manage it.

Many also spoke of vivid inner imagery and moments of intuitive knowing. The authors were careful to frame these not as messages from elsewhere, but as what can arise when the brain’s usual filtering and analytic grip quiets. When narrative and prediction loosen, perception can feel unusually direct, unmediated, and meaningful. What stands out is that these states were not described as empty voids, but as expanded awareness, where boundaries dissolve, and experience feels wider, more connected, and quietly alive.

Seen this way, the Gateway findings read less like an attempt to escape reality and more like an early exploration of what reality feels like when its usual mental construction softens. Beneath the language of fields and resonance lies a simple observation: when the mind’s ordinary frames drop away, what remains is not nothing, but a form of direct presence — a way of perceiving before it becomes owned by a self or organised into a world.

In the language of the brain–mind model, what the Gateway Researchers were touching was not a realm beyond reality, but the near-zero end of a sliding scale of experience — the physiological–perceptual collapse window we call the GAP, where perception loosens before it becomes a world again.

It is important to say, though, that this reading of the Gateway Process is not what its authors in 1983 were trying to do. At that time, predictive coding had not yet been established, the default mode network was unknown, the timing of conscious integration was only dimly understood, and ideas of collapse and reset were not part of mainstream neuroscience. They were working without a structural map of how experience is assembled in the brain–mind, and so they reached for the metaphors available to them — resonance, fields, holograms — to explain what they observed. What this article does here is not correcting them, but completing the picture: taking the phenomena they encountered and placing them within a model of perception and reset that simply did not exist then. In that sense, this is the same exploration, but carried one step further — from experience to structure, from metaphor to mechanism.